Lee Tran Lam Would Like To Eat With Tetsu Kariya

(This interview was transcribed and edited)

Hi Lee Tran. What do you do and when people ask you where you’re really from, how do you answer?

I’m a freelance journalist. The good thing is I haven’t had that other question about where I’m ‘from' for a while, which I always got a prickly feeling about being asked. Once, some guy at uni asked me and I was like, ‘Oh, from my mother’s tummy’, like I was trying to shut it down with a weak joke - but he kept persisting. There’s something about that persistence that anyone can relate to if they’ve dealt with that question. It’s basically, why aren’t you white? and please give me a very thorough breakdown of your family tree, even though we just met. That’s really what the question is. There was a period where it was always taxi drivers asking me, where are you from? And I’d say, ‘My parents are from Vietnam and their parents are from China’. If you actually analyse that, I’m not saying where I am from.

Where are you based right now?

I’ve always lived in Sydney. There’s a tendency in Australia now to say the traditional Aboriginal or Indigenous name, so I’m currently on Gadigal country of the Eora nation. I was born here and haven’t lived anywhere else.

Tell me about your job as a freelance writer.

I’ve written for a variety of mainly Australian media such as SBS Food, Gourmet Traveller and Guardian Food, and I recently did a story for the BBC that was about 100 years of Vegemite. It was not only exploring Vegemite, which has a very fascinating history, but a lot of it is so tied up to Australian identity. Australian celebrities are always asked about Vegemite, and when celebrities come here they always eat Vegemite to get on side with everyone. In the very early days of the pandemic when Tom Hanks put too much on his toast on Instagram that was an international incident! I also really enjoyed talking to chefs who use it in multicultural ways that reflect their heritage. There was Khanh Nguyen, who has just finished at Sunda - he’s famous for his Vegemite curry and sold 20,000 servings of it. It’s such a Melbourne dish that people know. Khanh talked about how he remembers having Vegemite for the first time when he was growing up, being blown away and going home to tell his Vietnamese parents. Vegemite has that pungency that’s something like Vietnamese shrimp paste. He talked about how his parents got the ratios all wrong, and put him off Vegemite for a long time! I also talked to Hetty McKinnon who has Vegemite miso instant noodles in her To Asia with Love cookbook. She spoke about how Vegemite is a way - especially for kids from migrant backgrounds - to bridge different cultures; the one they’ve grown up with but also the one they’re trying to become a part of.

I love Vegemite. I fell in love with it in Australia!

Are you allowed to say that? Isn’t it treason if you like Vegemite…

Yes! It’s different to Marmite for sure.

So how did your Vietnamese Australian upbringing influence your interest in food writing?

My experience is a very classic migrant kid experience. When I was growing up in the ‘80s there was definitely no representation. I remember on Neighbours there was a Chinese family (this is an infamous incident in Australian pop culture history), called the Lim family. One of the subplots was whether they ate the neighbourhood dog or not.

Oh man.

Exactly. Of course, they didn’t eat the dog - that’s just a stereotype that Chinese people eat dog - but, someone did point out that that family didn’t last very long on Neighbours and the dog Holly had a much longer life. So you grow up consciously or unconsciously disowning your own cultural background because you don't really see it reflected around you.

When I was growing up - in a suburb called Cabramatta - I was so embarrassed that we didn’t even have a McDonald’s. At the time I didn’t understand that being able to go out and get bánh xèo or buy a rambutan or lychee from the local grocery was pretty awesome. But at the time, because mainstream culture wasn’t showing you validation for that kind of food culture, you felt embarrassed by it. Of course, now I’m older, I’m like, who wants a McDonald’s in their suburb when it’s everywhere!? It’s more awesome to have a place where you can get good bún chả or avocado shakes.

It’s similar in London, being this very metropolitan city, where our cultural currency is in knowing good eats, specifically from diverse cuisines. How does that sit with you? Do you think it’s OK, the way in which a culture can become commercialised very quickly?

I think people have a wide range of complicated feelings about this. It’s a question of who benefits from this coverage? Obviously it’s different if it’s a mum-and-dad owned phở restaurant that’s been running for 30 years. That’s cool - good on them. They deserve the spotlight. But when, for instance, this controversial bar opened in Melbourne whose theme was the Vietnam War - they were using napalm imagery, bullets etc. and people were rightfully outraged. It’s like, how can you use something that caused a lot of trauma, tragedy and death as the edgy theme for your bar? The people were some white guys who eventually apologised.

I think there’s also room to cook outside of your culture if you do it with respect and cultural context. It’s interesting, especially within Asian cultures, when you have someone with Vietnamese heritage perhaps, who might cook something Japanese or someone from a Filipino background who cooks something Indonesian. There’s interesting interplay that can be done with respect.

Glad you said that. I keep an eye on the kinds of conversations that are around gatekeeping, especially appropriation and authenticity. I find that we are constantly focusing on the wrong part of the argument and asking the wrong questions. And if you gate keep, saying that white people can’t cook Vietnamese food, then what you’re also saying is ‘Vietnamese people, stay in your lane!’

Exactly. Cultural curiosity is a good thing we should welcome. A good example of this is how Japanese food draws on different influences. I’ve had the best pizza of my life in Japan. I’ve talked to Italian chefs who agreed that the best pizza you can get is specifically in Tokyo. Some of these pizzaiolos haven’t been to Naples, where pizza is from, but they just have such respect for how pizza is made. They’re not saying, ‘We make better pizza than the Italians’. They’re just saying, ‘We love pizza so much that we want to pay tribute to it’.

Look at how the Japanese do spaghetti napolitan, which is not really an Italian dish but comes from tomatoes being very expensive from post-war shortages. They’re making a version of spaghetti with bottled tomato sauce that tastes different from Italian spaghetti, but I personally find it delicious. There are lots of interesting things that can come out of cross-cultural influences; look at Filipino cuisine.

There’s colonisation…

Exactly, whether by force or by invitation. But a lot of positive stuff can happen if it’s done with respect.

So, do you also have this nebulous genre of ‘Asian’ food in Australia and where does it sit in the hierarchy of immigrant foods?

In 2018, Colin Ho and Nicholas Jordan wrote one of the most consequential pieces of food writing for the ABC, exploring why it was that Asian food or Asian restaurants don’t win awards. In it, award-winning chef Dan Hong says: ‘Why would people pay $30 for cacio e pepe, which is really just pasta, black pepper and cheese, but they won't pay more than $10 for three amazingly made har gau or xiao long bao, which probably require a whole lot more skill than making pasta?’

And if you looked at all the main restaurant guides, aside from high-end Japanese sushi restaurants, Asian food would always be in the cheap eats section. There was a really damning statistic about how Italian food is sometimes overrepresented in these awards and restaurant guides and the listings for all the Italian restaurants outnumbered all the Asian cuisines.

It’s pretty eye-opening. We’ve also seen this in American and English food coverage. I think Eater pointed out that for five years there was only one mainland Chinese restaurant in the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list… and it was an 800 dollar dégustation menu run by a French guy. One of the best restaurants in Sydney is a Malaysian place called Ho Jiak. The owner told me he gets so much pushback from Malaysians, who are the harshest critics and who tell him he shouldn’t be charging this much.

Malaysians and Singaporeans are the harshest on their own people! They constantly compare it to hawker prices back home.

With the example of Ho Jiak, we’re talking about rent right in the middle of Sydney. It’s just hard to compare to a little market stall run by one person.

What does the East and Southeast Asian population in Australia look like? It's mainly ethnic Chinese and Vietnamese?

Obviously after the Vietnam War there were a lot of Vietnamese refugees. Then there is a strong Chinese population. If you look at food, there’s a strong Thai restaurant scene. Every suburb has a Thai restaurant. Filipino restaurants are coming up.

I guess that’s because of the Thai gastrodiplomacy, and how much people from Australia travel to Thailand.

Can you tell me about how people self-organise or self-identify? Would you say you are Australian Asian or Australian Vietnamese?

I’ll probably say Asian Australian. I felt a bit fraudulent when I was growing up because my parents only spoke Vietnamese to each other. They never taught us. And when you’re growing up, you basically want to be a white kid so you’re learning all about other cultures. I kind of wish I could hit rewind and learn more about Vietnamese culture - I know so much more about French history than I do about Vietnamese history! But it also feels a bit like homework I should be better at. You know what I mean?

I know from speaking to my friends who have Vietnamese refugee parents,that they do not open up and talk. Trying to get those stories out of them in a sensitive and compassionate way is very hard, certainly different to other diaspora kids.

Yeah. There are so many stories I had to drag out of them. Also, there are things I’m naturally interested in - like learning Japanese because I wanted to be able to read manga, and I’ve visited Japan eight times, I guess because there’s no cultural baggage attached – like if I pronounce Japanese badly, there’s a sense that ‘at least I’m trying!’, but if I pronounce Vietnamese badly, it’s ‘embarrassing' because of my Vietnamese heritage.

Are you seeing a movement among the younger Vietnamese generations to reclaim and reconnect with their heritage through different touchpoints, food being one of them?

There’s definitely a lot more of that. I see a lot of people putting their Vietnamese, Chinese or Japanese names in their Instagram profiles next to their western names. It’s really awesome. I’m glad that people younger than me didn’t have to grow up in a culture where a Neighbours storyline about the only Chinese family was about whether they ate the dog or not!

Did you have a Westernised name or were you always Lee Tran?

So, this is interesting. Growing up in Cabramatta, which was so multicultural, you’d get on the bus and sit next to someone who was from Cambodia or someone from what was then called Yugoslavia. Everyone had a name like Lee Tran. Then when I was 11 I moved to a school closer to the city with a strong Italian population, and at the time I thought, maybe I’ll just call myself Lee as that’s easier. Then people would call me Lee Lam and I was like, I don’t want to be Lee Lam. That’s not for me.

Around uni time, I was like, my name’s LEE TRAN. I find that even if I exchange 20 emails with someone and they still call me Lee, at what point do I need to say, ‘Sorry, but that is not my name’? Sometimes you have to come up with tactics to diffuse it with some humour, like I’ll say, ‘I know it’s a confusing name - blame my parents’. I wish I didn’t have to do that.

That’s already very generous of you. Granted it is confusing because of that Chinese naming system where the last name comes first.

I often say to people who are about to have kids: please give your child a name that’s not too creative or give them a lifetime administrative headache. I’m not saying: don’t give your child a name of cultural significance; more to think about the life implications of giving them a name from Game Of Thrones or whatever.

Tell me about your Diversity in Food Media project?

Around three years ago there were a lot of conversations about representation and whose perspective gets covered, who gets a platform. A bunch of us freelancers started talking about how to improve diversity in food media. It is hard because we’re freelancers - I’m not an editor with the power to go and commission awesome writers. I started an Instagram account profiling people who deserve to have a bigger following. An Instagram page is low effort but has a decent impact. Then I edited the first New Voices On Food book with Somekind, a crowdfunding publisher that was started in March 2020 to help restaurants that had to shut down when Australia went into lockdown. The book promotes and supports new and emerging writers from underrepresented backgrounds.

Some nice stuff came out of it. Rosheen Kaul who was in the first book wrote this great piece about growing up in Singapore where she grew up chomping on little dried fish, drinking icy lime juice and all these vivid dishes, then coming to Australia where all the food was beige. But over time she got to appreciate it. So she came to prominence with her Isol(Asian) Cookbook, and now her Chinese-ish Cookbook has been nominated for a James Beard Award. That would have happened anyway, but it was great to have one of her earliest stories published in my book. . So it’s been really cool to give people that kind of opportunity.

I did the second book last year and recently got asked to guest edit the Lunar New Year features section of Gourmet Traveller, and I asked some of those writers to contribute. But I’m also aware that I’m just one person. There are lots of other people doing lots of other things. It’s important to impart that we are a bunch of people who have no money and no resources, who just deploy what we have.

One of my favourite stories is about Candice Chung who, when she got married, asked people to donate to a fund instead of having a wedding gift registry, which would administer cultural grants to upcoming young talent. In the end, she collaborated with SBS Food and raised a substantial amount of money, organising a big competition that included a writing, podcast and visual arts element. Many people got published through this initiative.

We have similarities in what we do, in terms of facilitating, organising and creating resources. Did you ever get paid? I find there’s a lot of unpaid labour and in the end it’s the POC who are the ones constantly being asked to donate and mobilise. It’s nice that Candice did that, but she also could have just enjoyed her wedding gifts! Do you see the establishment pulling their finger out?

The difference between when the first book came out and when the second book came out is really interesting. We were really lucky that when the first [book] came out, there was a bit of a moment. Cynics would say people felt like they should be seen doing something or vaguely caring about diversity. I remember Stephen Satterfield talking about how he had a massive bump in subscriptions for Whetstone Magazine, and he was like, ‘Well, I’ll be interested to see if that continues next year.’ We were really lucky. There was this sense of momentum, people being supportive, and giving us coverage or posting on Instagram.

I just found it so much harder to get the second book on people’s radars. It was a different situation; when the first book came out people were in lockdown, not doing as much. It just felt ten times harder. I also get that for the first thing you do, you’ll probably get the most attention for it, and by the time the second thing comes out, it’s not a novelty anymore. But it was interesting to see who supported the first book and continued to support the second book. I am so grateful for those people.

That lockdown period was like a zeitgeist moment, maybe you found this too, when you were put into the limelight to speak. I did feel slightly tokenised because I was being put in the limelight for doing what I’d been doing for a while. But I also used the attention to organise and fundraise. Coming out of the pandemic it’s been harder than being in that bubble. That’s why I’ve found it’s so important to build a strong organic community and to know your audience. My core group of supporters are East and South East Asians. It reminds me that what I’m doing is by and for us.

It's really tricky, there are times when you’re aware that maybe someone just wants you to be the tick on their diversity box. How much do you play along with that? Or should you just take advantage if that helps to spotlight people who deserve more attention?

I was recently reading a top 100 list of restaurants in Sydney. Thirty-three of those restaurants were in the eastern suburbs, which is a very white, affluent area. There were zero restaurants from western Sydney, which has much more of a migrant population and cultural diversity. Wow. Then there were restaurants in the Hunter Valley, which is a regional holiday destination, and the Blue Mountains, which is an hour out of Sydney, also a bit of a holiday destination. So there were more restaurants in these day trip areas two hours out of the city than in western Sydney. That’s when you realise there’s so much progress still to be made. But it's also hard when you work in media and you’re freelance. How do you critique these things without completely burning all your bridges and never getting any work again?

Are you interested in building your own ecosystems, like starting a Substack or similar?

Just putting those two books together in the last three years and doing that competition with SBS took up lots of energy. And being a freelancer is not the most financially viable situation in the world, especially as a journalist watching all the outlets around the world just disappear. You’re trying to survive, and then you’re trying to do these things. In a perfect world, I would be able to devote so much more time to Diversity In Food Media. But I also have to make sure I pay my rent and not be overrun by dirty dishes in my kitchen, do the laundry and... there’s a lot. I wish it was a little less hard. That would just be awesome.

Onto Asian slaw. Do you have this dish in Australia?

It feels like a generic thing where maybe I had it at a pub. It’s not something memorable, and probably had Japanese mayo in it - round about the time everyone started putting Kewpie on everything.

It’s an American invention that actually did start in a famous American Chinese restaurant. It was originally called Oriental Chicken Salad, and eventually it’s just become Asian salad or Asian slaw. You would actually have it without mayo because it’s become associated with health; the dressing is just soy sauce and sesame seeds, that kind of stuff. So I’m interested in how we came to put this vague racialised, ethnic term ‘Asian’ in front of slaw, or chicken, or noodles.

I’m not a scholar on this topic, but it feels like 10 years ago when you went to a pub and your tacos would be a taco, but it was also not a taco. I’m all for cross-cultural innovation, I’m not saying everything has to be done the most traditional way, but it’s a very generic thing of putting x, y and z on tacos without thinking about the history of the food. In the last five, 10 years we’ve had more chefs with Mexican heritage come to prominence and put tacos on the menu that reflect very specific parts of Mexico that they grew up in.

This may be very tenuous, but there’s a recent article that talks about how everything around the world is the same, whether it’s AirBnBs or cafes. I think of Asian slaw like that. Like the ‘everythingification’ or…

The homogenization of global culture!

Yes!

So are you a fan of cabbage?

It’s funny, you’ve asked me at a point when I’ve recently become obsessed with this Japanese cabbage salad called yamitsuki (やみつき) cabbage that I came across at two Sydney yakitori restaurants: Yakitori Yurippi and Yakitori Jin. It means ‘addictive addictive’. The first time I saw it on the menu I felt like, that’s hyping yourself up calling it an addictive cabbage salad! Then I realised it’s an izakaya staple. Yamitsuki is raw cabbage dressed in sesame oil, which really focuses on the nuttiness of the sesame, then flavoured with shio kombu. It’s salty and savoury and a bit sweet. I also remember once trying a dish at one of those Japanese izakaya restaurants - it was raw cabbage dipped into a chunky miso dip. It was so good, so delicious.

I love that raw cabbage you get on Thai salad platters, that you dip into that funky, umami, spicy nam prik. You need that blandness.

So you would like to submit this yamitsuki cabbage to the Asian Slaw Alliance…

Can I make a slight amendment? I’d like to do it in a way that represents what I’m interested in, and acknowledges that Australia is home to the oldest, continuous civilisation on the planet, which is the Indigenous First Nations people, with 65,000 years of knowledge and culture. Only in recent years have people started acknowledging that, and there are native ingredients that are becoming widely known, though Indigenous people should be benefiting from the profits of these bush foods. Currently it’s only around 1% that goes back, and that’s a travesty.

The cabbage dish needs something like lemon myrtle, which is an amazing citrussy, lemongrass-y ingredient that’s a bit floral. It’s delicious in chocolate and so many things. A lemon myrtle mayo could go well with it.

Who would you invite to eat this dish?

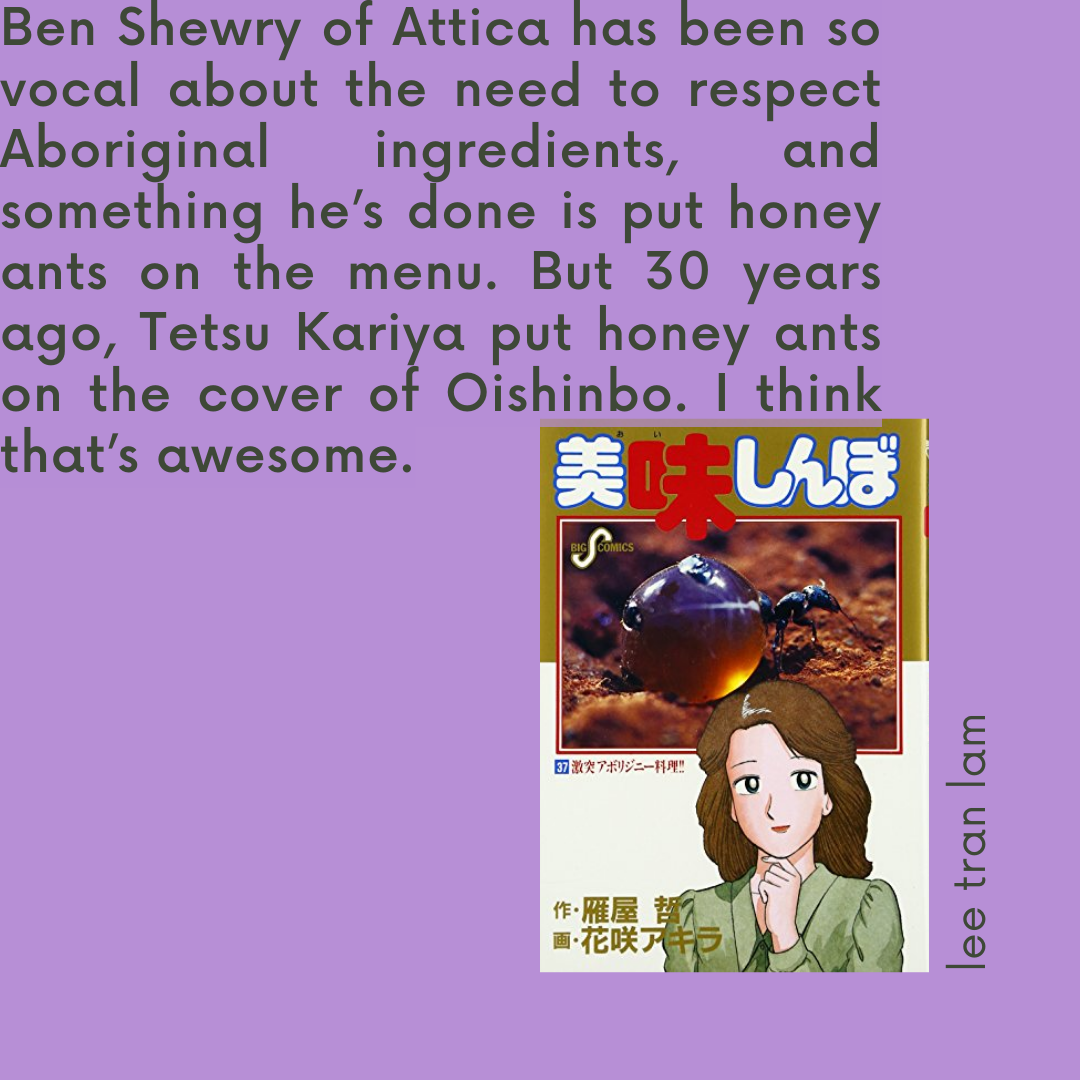

Tetsu Kariya, the writer of Oishinbo, the most popular food manga in Japan. Oishinbo started in 1984 and sold more than a hundred million copies. He’s lived in Australia since 1988, but has kept doing these very Japanese stories. An amazing story is that in the ‘90s he did one edition about the incredible history of Aboriginal cuisine, and how just like the Japanese they have such a reverence for their own cuisine. And that was at a time where there was a lot of racism about Aboriginal food; people being like, why would you eat grubs, and not recognising it for its richness, diversity and traditional knowledge. I spent the last week trying to track down a copy of it. Today one of the most famous Australian restaurants is probably Attica, run by Ben Shewry and it’s been on Chef’s Table and was on the World’s 50 Best list. Shewry has been so vocal about the need to respect native ingredients, and something he’s done is put honey ants on the menu. But 30 years ago… Tetsu Kariya put honey ants on the cover of Oishinbo - 25 years before Attica! I think that’s awesome.

The other Australian reference he put in Oishinbo, which is mainly set in Tokyo, was during the ‘90s when Pauline Hanson came to prominence as a politician and in her maiden speech complained that Australia was in danger of being ‘swamped by Asians’. That led to horrific things; I remember reports of someone at the art gallery of New South Wales getting spat on because they were Asian. Oishinbo also had an edition where they address Pauline Hanson. And the reason Oishinbo finished in 2014 is that Kariya did an edition about the characters going to Fukushima and getting nosebleeds, which was an after effect of the nuclear disaster [in 2011]. This caused a major outcry in Japan; even the Prime Minister weighed in.

So I’d love to have this cabbage with Tetsu Kariya, who’s incredibly political, non-apologetic and forthright about his views.